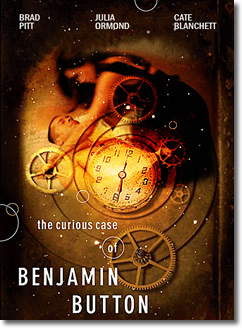

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

© 2008 The Kennedy/Marshall

Company

© 2008 The Kennedy/Marshall

Company159 minutes

How many molds remain for Brad Pitt to break? He’s not your “actor’s actor” – for now everyone’s giving that honor to Philip Seymour Hoffman and Meryl Streep— but he does have a certain knack for picking roles that ultimately fail to define him. When you add up the characters he’s played — criminals, cops, dunderheads, psychos, insubordinate sons, and at least one ancient Greek — you find no easy summation. Other than playing strongly masculine roles, he has simply left the confines of typology.

Well … there is that one thing. Quite often his characters seem to suffer from a certain wilting self-confidence. However, he seems to understand the trait competently enough, and has become accomplished at turning said hubris into consciously wrought black comedy (Burn After Reading, Fight Club) or tragedy (Se7en, Legends of the Fall). He’s made a career out of alternately burnishing his ego, then setting it ablaze.

I’m not so sure that’s a bad thing, though, and really, what would you expect from an actor who needs to trade on his looks (and thereby a self-mocking excessive pride) for as long as nature will allow it? For one day he will cross the same invisible transom over which Robert Redford and Paul Newman stepped in their day (from which point forward he will be known as handsome), and by that point we will need to see him—well, if not exactly as an actor’s actor, then at least as an actor in his own right, matured and settling and prepared to accept the mantle of a cinematic workhorse.

As if to (re)acquaint us with both the known past and the imagined future, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button gives us Mr. Pitt in full range, from decrepit to teenaged, offering whenever possible the actor himself. (Six other actors portray his character in the furthest extremes of old age and youth.) His character, the titular Benjamin, experiences the fullness of age in a sweeping but quietly epic way true to classic cinematic form, birth to death; yet he does it in reverse—as a little boy in an old man’s body, then as a mid-lifer in a mid-lifer’s body, then as an old man in the body of a teenager, a little boy, and finally a baby. The changes are many and subtle, intended to make us find ourselves wondering about how it is that time works, and how we’re meant to work or not work alongside it as it relentlessly unspools.

The conceit is successful. It succeeds because of the efficiently startling (but not overpowering) computer and makeup effects. And because Mr. Pitt knows that his reverse-aging body is the place where our wonder is meant to land and stick, and he carves out of Eric Roth’s screenplay the taciturn and likeable character in whose shoes we journey.

The film also works because it knows what it is, and director David Fincher has no need of it being anything else. In both artistic and literary terms, it seems long settled within itself. Because of its scope and setting, it has invited certain comparisons to Forrest Gump. While such comparison is not totally unwarranted (both are historic and Southern), Benjamin Button works efficiently and sensitively without all the sideshow bluster or flat comedy of Gump. It is as though someone gave Forrest some Ritalin and taught him how to meditate.

Even so, Benjamin’s life is not itself uneventful. It is, rather, a strange story of a strangely arranged person to whom random chance is well known. (The line, “You never know what’s coming for you” is often repeated— similar to but better than “Life is like a box of chocolates.”) Still, it’s not a dark or worrying fatalism; and at times Benjamin and those around him articulate their trust in the providence of God. With the things that happen to Benjamin, there’s a sense of evenness about all this: for at the same time that the film begs to know why things happen, it’s also honest in saying that there just aren’t easy answers.

In one exemplary moment, the events that lead up to a tragedy are listed: “A” through “Y” had to happen in order for “Z” to occur, and isn’t it kind of sad how it all lined up? But in the same breath, no one is looking to put the blame anywhere. Good, bad, or indifferent, it all just kind of happened, and here are the results. The film’s spirituality – and yes, it has one – is not so much in contemplating the Grand Plan (if such a thing there be), but rather in looking at what’s been handed to us and asking, Well, what shall we do now?

“No man and no destiny can be compared with any other man or any other destiny,” Viktor Frankl wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning. “No situation repeats itself, and each situation calls for a different response. Sometimes the situation in which a man finds himself may require him to shape his own fate by action. At other times it is more advantageous for him to make use of an opportunity for contemplation and to realize assets in this way. Sometimes man may be required to simply accept fate, to bear his cross. Every situation is distinguished by its uniqueness, and there is always only one right answer to the problem posed by the situation at hand.”

This is chiefly what distinguishes the characters of Benjamin Button and Forrest Gump from one another. Forrest is someone to whom history happens passively. His mostly toneless uniformity is the joke. He does not experience substantial change or growth. (His last name is a clue to how stuntedly he approaches his life.) Benjamin, too, is the recipient of history, but when it happens he seeks to understand it, integrate it, and move forward with it. Forrest is an impenetrable monolith; Benjamin is subtler. He cannot be the same from day to day because the world and the people in it are changing all about him, and to ignore that fact, as Frankl pointed out so beautifully, would be failing to “shape his own fate by action.”

That’s why Benjamin needs to be played by a mold-breaker. His role is wrought with change—interior changes marked by exterior changes. Similarly, the film itself changes in tenor several times: locations, time periods, principle characters, motivations. So unless we’re willing to adapt to this ethos, then we are in for a slog of almost three hours.

Ultimately, what we have here is an invitation to use another’s life to assess our own: How do we deal with change? How do we account for it? What patterns do we fall into or out of when life reshuffles itself and throws out a new hand? Will we blame God and rage and foam and retreat further into ourselves, or will we embrace What Is and seek another tack? Will our trust be broken or built up?

‘Course, you don’t need a film to make you take such stock of your life and spirit and habits. Then again, you never know what’s going to be thrown at you when you put yourself in front of a movie screen. But if you aren’t a little different when the lights come back on, why’d you go in the first place?

Copyright©2009 Torey Lightcap